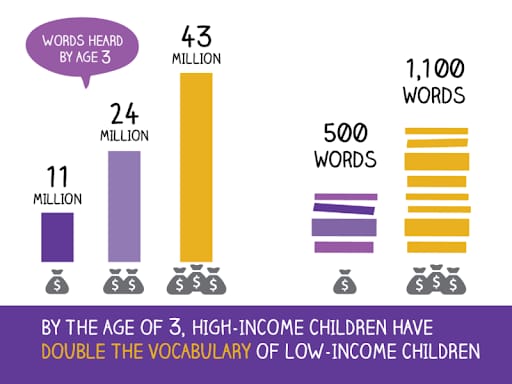

You’ve probably seen diagrams like the one above, and heard about the “word gap” - the statistic that lower-income children hear 30 million fewer words than wealthier peers during early childhood. This statistic is often used to explain why kids from low-income backgrounds show weaker language development by grade three. But is it really that straightforward? Does more word input automatically equal better language gains?

In my work running a global literacy nonprofit, this statistic came up regularly, and I worried about how best to increase word input for the most marginalized children in our programs. However, a fascinating paper by Rowe and Snow (2020) showed me that the “30 million word gap” might not capture the whole story—and revealed three deeper dimensions we should consider when designing effective literacy and language inputs for early childhood.

What Really Matters For Language Development

Rowe and Snow (2020) propose that quality of caregiver input – rather than just the quantity of words a child hears – is crucial for early language development. They organize the features of high-quality input into three key dimensions:

Interactive Dimension

This dimension centers on responsiveness and genuine back-and-forth exchanges. Children thrive when adults engage them in extended conversations, attending to their cues and following their interests. Rather than a single response, quality interaction unfolds across multiple “volleys,” creating a sense of mutual partnership in the conversation. To learn more, see this post on the power of serve and return interactions.

Linguistic Dimension

Here, the focus is on the complexity, diversity, and clarity of language that children encounter. Infants benefit from “infant-directed speech” (or “parentese”), which uses a slower pace, exaggerated intonation, and plenty of repetition (its that high-pitch, annoying voice you often hear parents use to talk to their babies - its actually good for them!). As children grow, they gain more from being exposed to an ever-wider range of words and sentence structures, rather than hearing the same phrases over and over.

Conceptual Dimension

Conversations vary in depth and abstractness, and this dimension captures how they evolve over time. In infancy, simply labeling or describing what’s right in front of a child helps build foundational language skills. Later on, introducing talk about the past, future, or complex “why/how” questions stretches a child’s thinking and promotes richer language learning.

The so-called “word gap” has long been blamed for literacy struggles, but evidence suggests a more nuanced story: it’s how we communicate that truly matters. Parents and caregivers in all kinds of households can spark a child’s language growth by creating rich, back-and-forth conversations.

My Insights

Emphasizing word input alone might overshadow the richer, more nuanced aspects of language learning. For one, parents may end up “talking at” their children rather than with them, reducing opportunities for genuine back-and-forth interaction.

It could also create undue stress or guilt, especially among families with limited time, who might incorrectly assume that quantity always outweighs quality. And from a policy perspective, focusing only on word counts can lead to interventions that miss the mark, ignoring essential factors like warmth, responsiveness, and conceptually challenging conversations—all of which truly propel language development.

The paper by Rowe and Snow also points out that culture, language, and socioeconomic status can lead to different patterns of caregiver speech. While the exact form of high-quality input may vary across contexts (e.g., some cultures use more direct instruction; others rely on child-led interactions), the three dimensions still apply. Noticing the quality of language input across these three dimensions, even in a variety of different contexts, is much more important than a singular focus on word input.

I’ve certainly been guilty of simplifying language development to a single stat—like total word exposure. But what we really need to emphasize is a principle that I keep coming back to across my research in early childhood: responsive interactions are key to helping children thrive.

Key Takeaways for Practice

What if we simplified the science to a simple rhyme that practitioners working with different ages of children could remember?:

Infancy: Frequent, contingent responses to an infant’s vocalizations and gestures help build early vocabulary:

“Sing and repeat, it makes words so sweet!”

Toddlerhood: More diverse vocabulary, longer utterances, and gently challenging questions (e.g., “why” questions) best support language growth:

“Ask them why, watch ideas fly!”

Preschool: Conversations that include explanations, narratives about past events, and hypothetical scenarios deepen children’s language skills and encourage more advanced cognitive development:

“Stories we share, build minds that dare.”

Research Deep Dive

The biggest myth is that children’s language outcomes rest solely on how many words they hear, especially in low-income homes. Research now shows that quality trumps quantity. Yes, children need exposure to words—but they thrive when adults (parents, caregivers, educators) engage them in natural, meaningful conversations. We need to shift the focus from “how many words” to the richness of these words.

Rowe and Snow’s core argument is that early language learning is driven by the quality of interactions, not simply the quantity of words. High-quality caregiver input is:

Interactionally supportive: fosters mutual exchange and responsiveness;

Linguistically adapted: uses speech that fits a child’s current level but pushes them forward;

Conceptually challenging: provides meaningful, often abstract or more advanced topics once children are ready.

This framework encourages parents, educators, and researchers to focus on how they talk to children—showing that nuanced, rich, and responsive engagement is key to fueling children’s language development.

References:

Rowe, M. L., & Snow, C. E. (2020). Analyzing input quality along three dimensions: interactive, linguistic, and conceptual. Journal of Child Language, 47(1), 5–21.

Share Your Voice

Please take 10 seconds to respond to this poll that way I can keep improving the newsletter for you!